Contribution of the Bed Nucleus of the Stria Terminalis to Fear Relapse in Rats

Dr. Careaga is a PhD graduate of Universidade Federal de São Paulo, Brazil.

Fear relapse is a major concern for fear-related disorders such as post-traumatic stress disorder. Even though clinical treatments such as exposure therapy may reduce fear-related symptoms to varying extents, fear relapse can occur at any time in many individuals. Therefore, it important to elucidate the brain processes that underlie the return of fear-associated memories in response to certain environmental stimuli and contexts. Prior studies had implicated a role for the Bed Nucleus of the Stria Terminalis (BNST) in the relapse of extinguished behaviors, including stress-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking. In their publication, Goode and colleagues investigated whether pharmacological inactivation of the BNST impacted both fear reinstatement and renewal.

In classical fear conditioning, rats can be trained to learn an association between an environmental stimulus (cue) and an adverse stimulus. For example, a conditioned stimulus (CS) such as an auditory tone or light pulse may be paired with a noxious unconditioned stimulus (US) such as a footshock. Upon learning the CS–US association, presentation of the CS alone elicits conditioned fear responses such as freezing behavior. Subsequently, fear extinction, characterized as a decline in the conditioned fear response, occurs with repeated presentation of the CS without the US. Extinction is thought to represent a new CS–no US memory that competes with the initial CS–US association to limit the expression of conditioned fear responses. As fear extinction does not erase the original fear memory, fear responses can return. Two forms of fear relapse are reinstatement and renewal. Fear reinstatement occurs when fear responses to an extinguished CS return following presentation of the aversive stimulus. Fear renewal occurs when the CS is encountered in a different context (characteristics of the physical environment) from the extinction context.

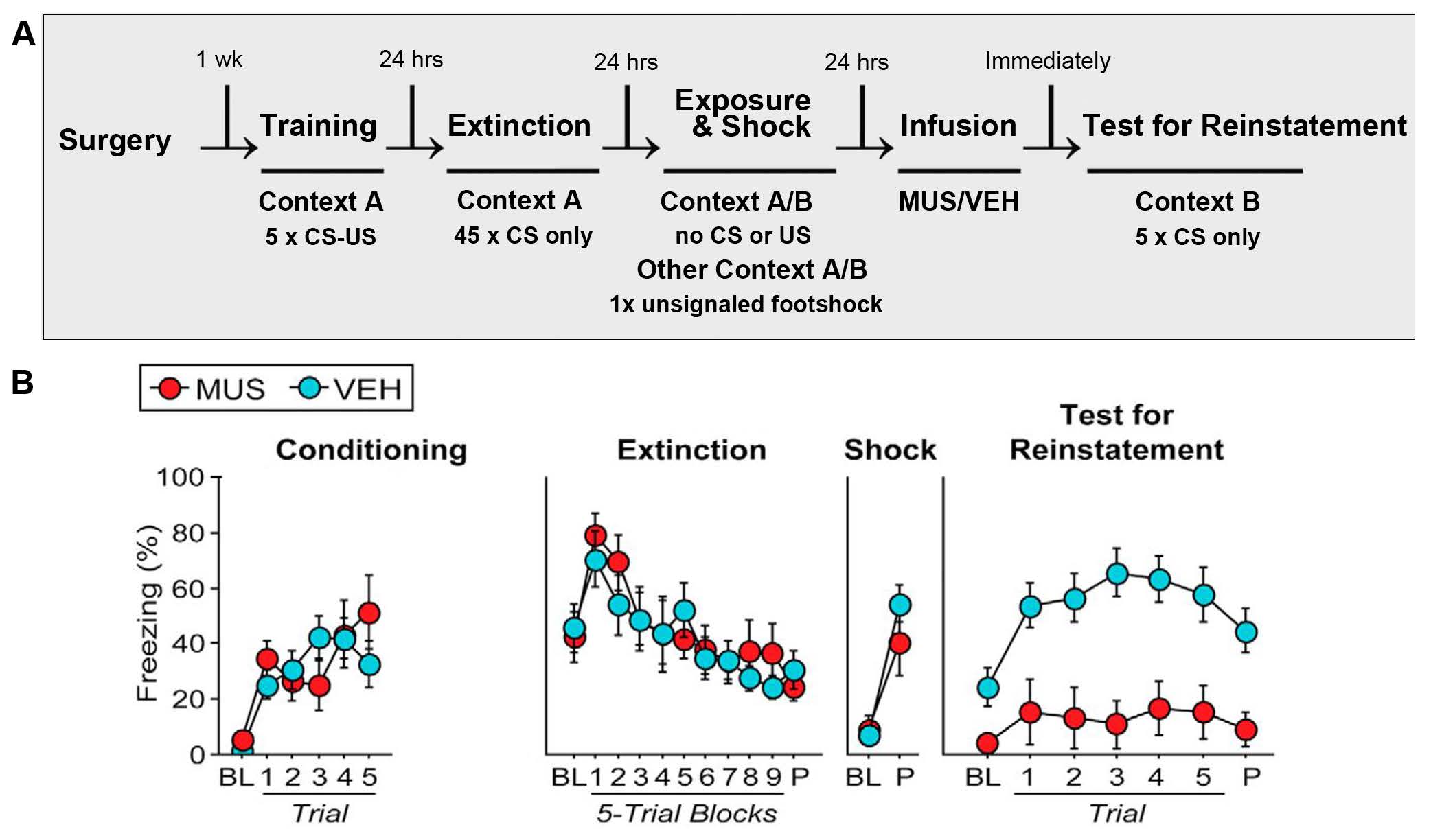

The authors used three chambers with distinct odors and visual cues to create Context A, B, and C. During a surgical procedure, cannulae were implanted in the BNST of adult rats, which was followed by a week of recovery. The behavioral paradigm for the fear reinstatement experiments is shown in Figure 1A. The rats underwent cued fear conditioning in Context A, during which an auditory CS was paired five times with a footshock US (5 x CS–US). On each of the following two days, rats underwent an extinction session in Context A, which involved exposure to the CS alone (45 x CS only). Following extinction, the authors evaluated the effects of BNST inactivation on fear reinstatement using a reinstatement shock session. The rats were briefly exposed to either Context A or B (no extinction in A/B) before exposure to the other context (Context B or A) in which one unsignaled footshock represented the reinstating shock. One day later, the rats were infused with either vehicle (VEH) or muscimol (MUS; a GABA-A receptor agonist) and subjected to retrieval testing in Context B to assess fear to the extinguished CS (5 x CS only). Freezing responses of VEH- and MUS-infused rats were similar during conditioning, extinction sessions, and reinstatement footshock. During the CS retrieval test, VEH-infused rats froze to a significantly greater extent in response to the extinguished CS than the MUS-infused rats (Figure 1B). These results show that BNST inactivation led to reduced fear reinstatement to an extinguished CS.

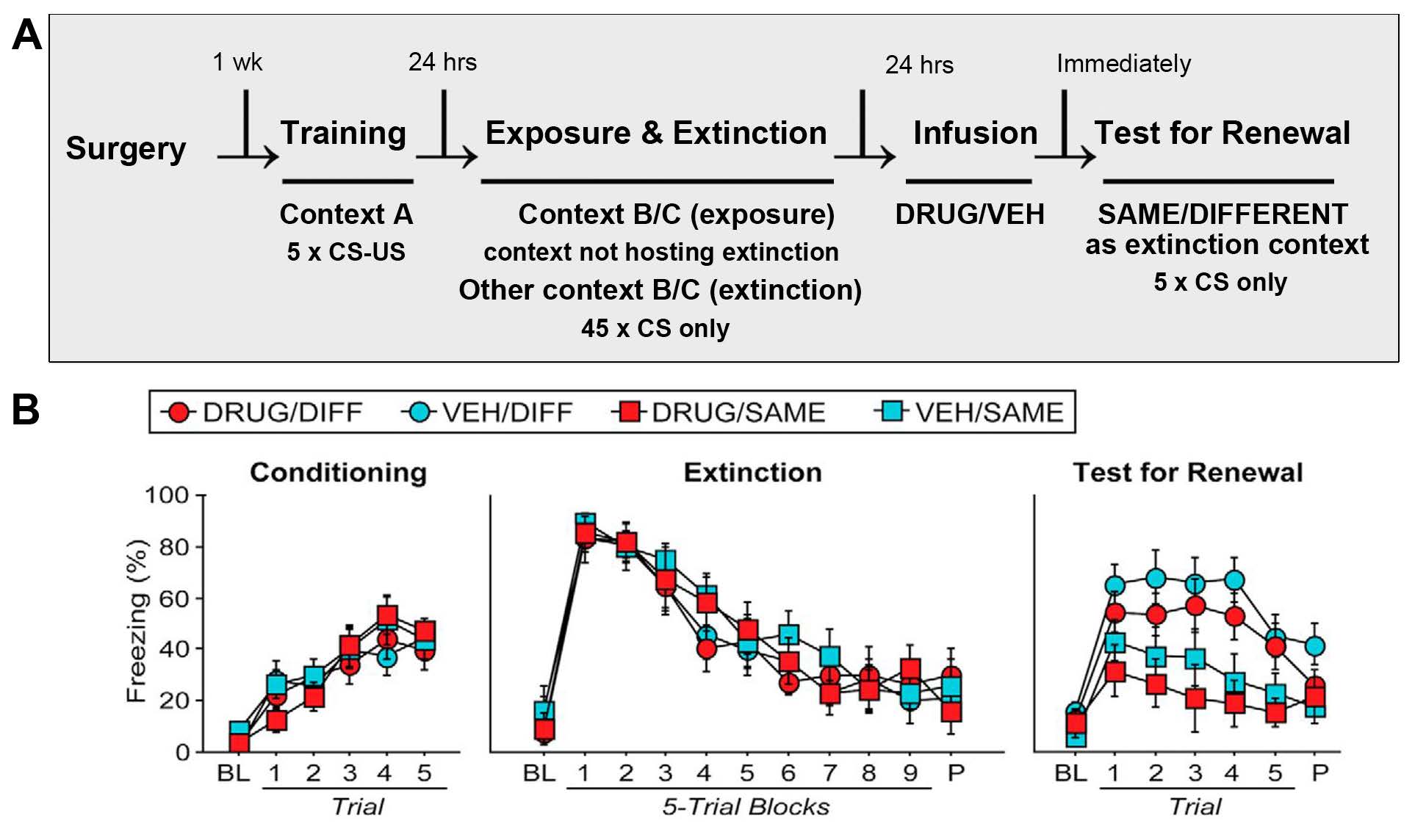

To investigate the consequences of BNST inactivation on fear renewal, a separate cohort of rats underwent the same surgical procedure and recovery as used for the fear reinstatement experiments. Rats were assigned to either VEH or DRUG groups. The DRUG group included rats infused with MUS or 2,3-dihydroxy-6-nitro-7-sulfonyl-benzo[f]quinoxaline (NBQX, an AMPA receptor and kainate receptor antagonist) as post-hoc analysis revealed similar results with either drug treatment. The behavioral paradigm for the fear renewal experiments is shown in Figure 2A. As in the prior experiments, cued fear conditioning occurred by exposure to 5 x CS–US in Context A. The next day, rats were exposed to either Context B or C (no extinction in B/C) before exposure to the other context (Context C or B) in which 45 x CS were presented to extinguish the fear response to the CS. One day later, and immediately before renewal testing, rats were infused with VEH or DRUG. Renewal testing was carried out by presenting 5 x CS in either the same or different Context (B or C) in which the extinction session took place. Before infusion, rats did not differ in freezing responses during the conditioning or extinction sessions. DRUG-infused rats that underwent renewal testing in a different context from the context used during extinction froze at similar levels to the VEH-infused rats exposed to the same condition during renewal. These findings suggest that BNST inactivation did not reduce renewal of fear to the extinguished CS (Figure 2B).

Goode and colleagues' publication showed that the BNST plays a role in the reinstatement but not renewal of extinguished fear. These findings suggest that different neural circuits are involved in different forms of fear relapse. Recent research in the laboratory of Professor Stephen Maren (Institute for Neuroscience and Department of Psychology, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX) has provided knowledge of the role of the BNST in response to unpredictable threat signals. Unpredictable threats refer to situations in which the fear-evoking stimulus does not accurately predict the timing of the adverse outcome. Goode and colleagues demonstrated that inactivation of the BNST reduced freezing in response to the CS when the CS poorly signaled US onset. Moreover, rats subjected to the unpredictable situation exhibited greater c-Fos expression (a protein used as a measure of neuronal activity) in the ventral BNST and in neurons from the BNST that project to the infralimbic region of the medial prefrontal cortex (Goode et al., 2019). The authors also showed that inactivation of the BNST results in impaired freezing to the context when it unreliably predicted the US onset (Goode et al., 2020). These recent findings reveal that it is not the length or nature of the CS that determines the involvement of the BNST in the expression of conditioned freezing. Rather, it is how reliable conditioned stimuli signal the occurrence of the US that dictates the recruitment of the BNST in the regulation of fear processes.

References:

- Goode TD, Ressler RL, Acca GM, Miles OW, Maren S. Bed nucleus of the stria terminalis regulates fear to unpredictable threat signals. Schoenbaum G, Dulac C, Schoenbaum G, editors.eLife.2019 Apr 4;8:e46525.

- Goode TD, Acca GM, Maren S. Threat imminence dictates the role of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis in contextual fear.Neurobiol Learn Mem.2020;167:107116.

This Reader's Pick was reviewed and edited by eNeuro Features Editor Rosalind S.E. Carney, D.Phil.

Read the full article:

Reversible Inactivation of the Bed Nucleus of the Stria Terminalis Prevents Reinstatement But Not Renewal of Extinguished Fear

Travis D. Goode, Janice J. Kim and Stephen Maren

FOLLOW US

POPULAR POSTS

TAGS

CATEGORIES

RSS Feed

RSS Feed