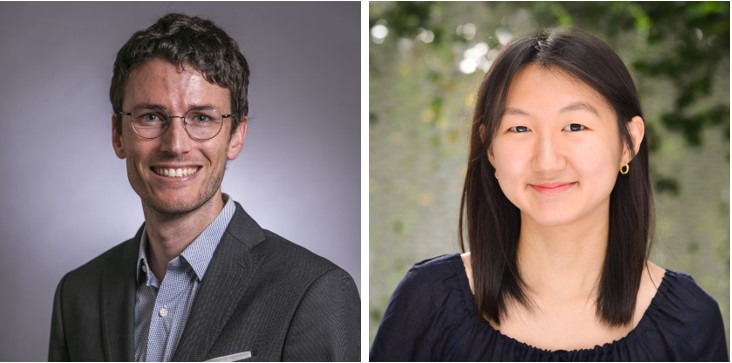

Beyond the Paper: A Conversation with Dr. Maxime Chevée and Ms. Courtney Kim

Interviewed by Dr. Paige N. McKeon, January 25, 2024

Reward-related behaviors can be classified as goal-directed, meaning organisms can control their pursuit of a reward when its value changes, or habitual, meaning pursuit of a reward persists even when the reward no longer has value. Research on these behaviors advances our understanding of how reward learning is altered in cases such as addiction or obsessive-compulsive disorder. In their co-first author paper, Chevee and Kim explored how different reinforcement training schedules, which are used for animal models of reward learning, and food restriction, which is often used during behavioral experiments to increase engagement with tasks, interact to impact reward behaviors. They found that food restriction differentially impacted behavior depending on the reinforcement training schedule coupled with it. Thus, the structure of reinforcement schedules and the use of food restriction should be carefully considered alongside an animal’s task engagement to appropriately draw conclusions about the neural underpinnings of reward behavior.

What drew each of you to pursue this particular line of research?

Maxime: I’m interested in understanding habits because they speak to how internal and external influences fundamentally change the way we control our actions. The flexibility with which our behavior adjusts to every situation is truly fascinating and drives much of my research interests. This project started from that interest, as the different schedules of reinforcement we describe in the study are typically used to bias control strategies towards or away from habits. However, when we tried using them, we noticed that they only worked if the cost inherent to each schedule was finely matched to the animals’ motivation levels. In other words, if the animal had too much or too little motivation to engage in the task, the schedule didn’t have a large impact on the control strategy. In our line of research, we often manipulate motivation by maintaining animals on mild food restriction, so we started thinking about the role of food restriction itself. It was a bit of a roundabout way, but that’s how we arrived at this study question.

Courtney: As an undergraduate student at the time, I had a broad question in mind of, “Why do we do what we do? How do our behaviors shift?” I think this curiosity was what made me join the lab and work on this project. As an incoming PhD student, I’m still formulating and streamlining my specific area of interest, but understanding how learning and behavior works fascinates me. Deriving specific types of behaviors with carefully designed studies, discovering variables that influence those behaviors, and finally, understanding how the brain brings along those changes are simply captivating. Motivated by our project, I’m now studying self-guided, exploratory behaviors in Dr. Richard Axel’s lab, and it’s an honor and a joy to crack the code behind animal behavior.

What are your future career goals, and how have your respective lab experiences informed where you see yourselves going in your careers (if at all)?

Maxime: I will be applying to faculty positions this fall – so I hope the future looks like a laboratory. My experience in the Calipari lab has been a time of scientific and career growth. During this time, I’ve tried to both learn the ropes of running a lab as well as develop the vision for my independent career. I hope my future research will focus on how changes in physiological states, such as energy balance or inflammation, trigger plasticity mechanisms in the decision circuits of the brain. I want this work to ultimately provide links between the physiological changes seen in many disorders and their impact on fundamental aspects of our behaviors.

Courtney: I’m starting my neuroscience PhD in the coming fall, and I’m trying to keep an open mind about what my long-term goal would be. For now, I’m interested in studying learning and behavior with the sensory system, and I want to adopt different perspectives whether it be a different model system or a different technique. I can say with confidence that my experience in the Calipari Lab made me realize that science is what really excites me, and it fueled tremendous professional and personal growth.

“We will certainly remain colleagues and friends for the rest of our careers.” -MC

“[...] working with Maxime taught me how to think like a scientist and appreciate the beauty of collaboration in science. In fact, our collaboration was the main catalyst for my decision to pursue a neuroscience PhD.” -CK

What was it like working together as co-first authors on this publication? How did your different science backgrounds and perspectives contribute to your collaboration?

Maxime: I enjoy mentoring undergraduate students. And I think Courtney and I worked together quite well. When she joined the lab, Courtney had an open mind about her future – upon graduating she secured a research assistant job and is currently interviewing for neuroscience graduate programs – so at least I didn’t scare her away! We will certainly remain colleagues and friends for the rest of our careers.

Courtney: Prior to joining the Calipari Lab, I worked in labs using C. elegans and humans as the model system, but not mice. Maxime armed me with all the necessary toolkits before we embarked on our project, and I appreciate him for that. From experiment design and execution to publishing, working with Maxime taught me how to think like a scientist and appreciate the beauty of collaboration in science. In fact, our collaboration was the main catalyst for my decision to pursue a neuroscience PhD.

Did the outcomes of the experiments in this paper surprise you? What challenges or surprises did you run into along the way and how did you overcome them?

Maxime: What really surprised us was the initial observation that response rates, as controlled by modulating levels of food restriction, dominated the effects in extinctions that are typically attributed to schedule. It made us realize that the relationship between sensitivity to reward devaluation and the dichotomy between habits and goal-directed behaviors was a little more complicated than we initially appreciated.

Courtney: When we tried to replicate the reinforcement schedules used in previous studies to derive habitual and goal-directed behavior, our results didn’t align with their findings. Our response rates were different within and across the two behavior groups compared to those of the previous results, and this is when we had to make a little tweak and think about the role of motivation levels. This observation was surprising and exciting at the same time as it became the main storyline of our project.

There were a lot of challenges along the way, from removing as much bias as we could when interpreting the animal behavior to actually carrying out the experiment and facing a myriad of technical issues. But watching the mice slowly learn and just simply observing their remarkable behavior patterns really made all those challenging days full of excitement.

“But watching the mice slowly learn and just simply observing their remarkable behavior patterns really made all those challenging days full of excitement.” -CK

In each of your opinions, what is/are the most valuable contribution(s) of this paper to the field and where do you see the project going?

Maxime: Hungry animals work harder for food rewards, which is intuitive. For me, the most interesting finding of our study is that this effect interacts with distinct schedules of reinforcement differently, both within sessions and across days. Therefore, simply restricting animals’ daily food intake (which is quite common across neuroscience studies) can have varying levels of influence on a behavior depending on the rules and timing of the task – something to keep in mind! As far as next steps, we are now looking inside the brain for clues as to what neural signals are being affected by food restriction to modulate learning rates.

Courtney: Now that I’m in the position of studying volitional behaviors, I have come to further appreciate the different covariates we explored in our manuscript such as the testing order. Animals already exhibit an extremely rich set of behaviors, and the most intricate factors will inevitably tip an animal towards different outcomes when you are trying to reinforce a certain behavior. I think our manuscript was able to explore that by adding a new perspective to the previously explored behavioral strategies for habitual and goal-directed behaviors.

“[...] simply restricting animals’ daily food intake (which is quite common across neuroscience studies) can have varying levels of influence on a behavior depending on the rules and timing of the task – something to keep in mind!” -MC

How was your experience with the eNeuro review process?

Maxime: The review process was very helpful. We actually had overlooked an important co-variate in our initial analysis. The reviewers pointed that out and it made the findings much stronger. The editor also gave us extra time for doing revisions when we asked – which was very much necessary and appreciated.

Courtney: I definitely think the review process significantly improved our study. It’s always helpful to receive feedback from the broader scientific community, and we were able to carry out additional insightful experiments and reframe some of our analyses.

Follow Dr. Maxime Chevée: @MaximeChevee

Follow Courtney Kim: @courtneyjkim

Calipari Lab Website: https://www.caliparilab.com/

Read the full article:

Food Restriction Level and Reinforcement Schedule Differentially Influence Behavior during Acquisition and Devaluation Procedures in Mice

Maxime Chevée, Courtney J. Kim, Nevin Crow, Emma G. Follman, Michael Z. Leonard and Erin S. Calipari

FOLLOW US

POPULAR POSTS

TAGS

CATEGORIES

RSS Feed

RSS Feed